“Family photography, as a genre, documents the ‘being with others’ of the domestic sphere,” writes Thy Pay, Elspeth H. Brown and Andrea Noble in their essay Feeling in photography, the affective turn, and the history of emotions.

“These photographs record what Catherine Zuromskis has called ‘aspirational fictions’ that allow us to record ourselves and our histories as we would like to remember them.”

The essay then goes on to suggest that “tears in a family photograph would most definitely puncture domesticity’s aspirational fiction”.

Other Mothers both carries and punctures an “aspirational fiction”, but what kind of fiction am I attempting to weave here and how can photography be used to explicate memory, suggest disruption and viewpoint and convey “feeling”?

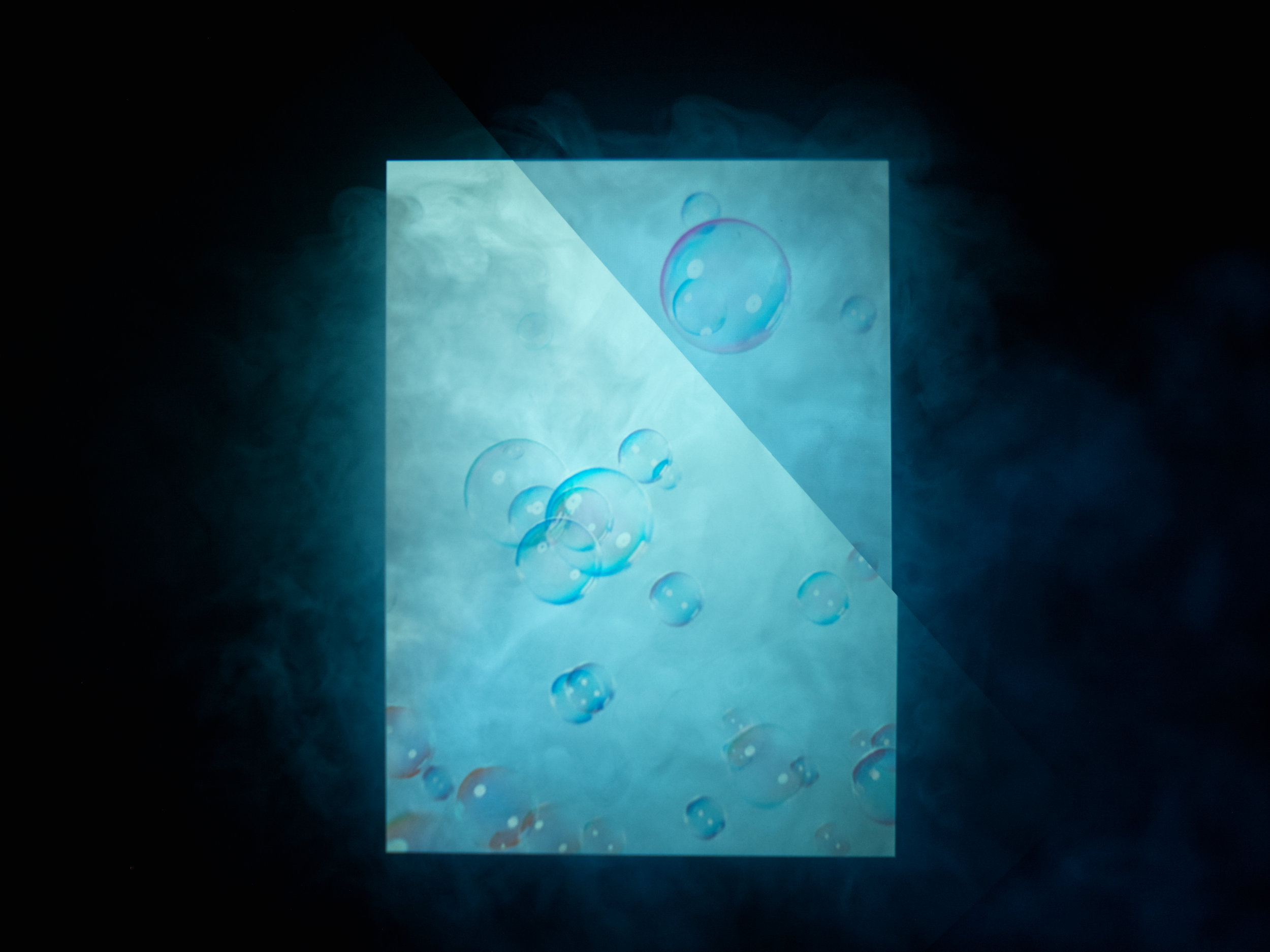

I’ve continued to explore my interrupted projections and attempted to do so with more purpose.

Each Other Mother was paired with a number of previous works from my After series which felt particular to them. In rephotographing the projections I was keen to use a different coloured (colour chosen again by what felt ‘right’ for each person) disruption board and held at a set distance in front of the main projection to create varying degrees of out of focus, to focus in on areas of importance and to work in various depths and densities of line shadows.

These line shadows, and the placement of the boards themselves, have become central to this project. Not only are they intended to reflect that inner sense of dissection I felt when my mother abandoned me, they do something else which has resonated very deeply with me, something that might best be explained by Lego.

I was obsessed with Lego when I was a young boy. It was, I now feel, a passion for manageable units. Entirety was daunting and frightening. Bringing something into being one block at a time, and altering one block at a time, was a means of coping.

Lego was also where I sought refuge from a chaotic world. This is something I am having to confront in this project. My father told me a few years ago that he was bi-polar. Although it did not have a name when it was just he and I in the late 1970s and early 1980s, it was always there.

Let me clear, he was an incredible father. When he was in a ‘good mood’, being in his company was (and is) the most special place on earth. When he was not, he would retreat, become difficult to engage with and become more functional in his parenting.

He says he always wanted to protect me from his ‘lows’. Now that I know how low the lows of a bi-polar person can be, he did. But I always knew that my father’s love had a rhythm, that it was not stable in its expression.

There were, therefore, areas of existence over which I had control and much where I did not. The motifs of smoke and fog have been used throughout this project to give some sense of this haze of my early reality, and to extend that space of uncertainty beyond the projected frame. The strength of its presence fluctuates throughout the series, according to whims of the fog machine…

References:

Pay, T, Brown, E and Noble, A (2020). Feeling in photography, the affective turn, and the history of emotions in Durden, M. and Tormey, J. (2020). The Routledge companion to photography theory. London ; New York Routledge, Taylor Et Francis Group.