I’ve begun to find the ongoing discussion about the impact of digital capture in photography really tedious. Fred Ritchen, in After Photography (Into the Digital), warns of “digital” photography as a “Trojan horse” that will both “end and enlarge” photography as “we have known it”.

He compares “analogue” and “digital” photography to vinyl records and iPods: “A vinyl record was created with the intention that it be experienced within the logic of a beginning proceeding to an end; a music CD or iPod is made to be resequenced, shuffled, and rethought.”

True, but where does that most common of teenage love tokens from my own youth – the mix tape – figure in this? That pre-digital mash-up that pre-figured (inspired?) the digital shuffle function? Or the immense popularity of the Top 40 broadcast into millions of homes every Sunday afternoon on Radio 1? And is not one of the great pleasures of vinyl landing the stylus exactly where you want it before the tune you desire to hear?

Ritchen’s concerns about this “digital revolution” centres around the “self-containment of this new technological universe”, the loss of human intent and engagement with image capture (“casually enacted using telephones and PDAs, webcams and satellites”), mass psychological damage from a superfluity of code and further commodification, or relegation, of our world (and those in it).

I share many of his concerns about this digital age, though mine are more of the societal/interrelationship/disinformation variety. I see my cameras – digital and analogue – as tools. But for the environmental strain of powering the storehouses of trillions of digital images, I don’t worry about the huge mass of people out there interacting visually with one another or the world they navigate.

Sure, much of the output might be trivial and nondescript, but so what? I wonder whether such concerns would abound if the whole world suddenly took up painting? Would we be fearful for the future of art in a world in which everybody had a paintbrush and used it? Yes, there would be a large amount of ill-thought out pieces created, many images of people’s cats and possibly more than a few selfies. And, yes, I would still have environmental concerns about the amount of pigment being used. But wouldn’t it be great if the whole world took up painting? Or writing? Why not image creation via digital device?

Moreover, I don’t see access to, and use of, such devices as static, as I feel Ritchen sees it. Learning and usage are a process. Many of those who use their devices for selfies or to document where they are and what they are doing develop skills and are keen to learn more and try new things. A few are likely to end up creating meaningful bodies of work.

Nor do I agree with this analogue/digital binary. My own children are among those Ritchen fears for – glued, as they sometimes are, to their screens. They also love mountain biking, the great outdoors and drama on stage. My daughter loves creating content for Youtube, Instagram and posing for selfies. But she also loves playing with my old Linhof and requested a basic manual Lomo film camera for her birthday and has loved experimenting with it.

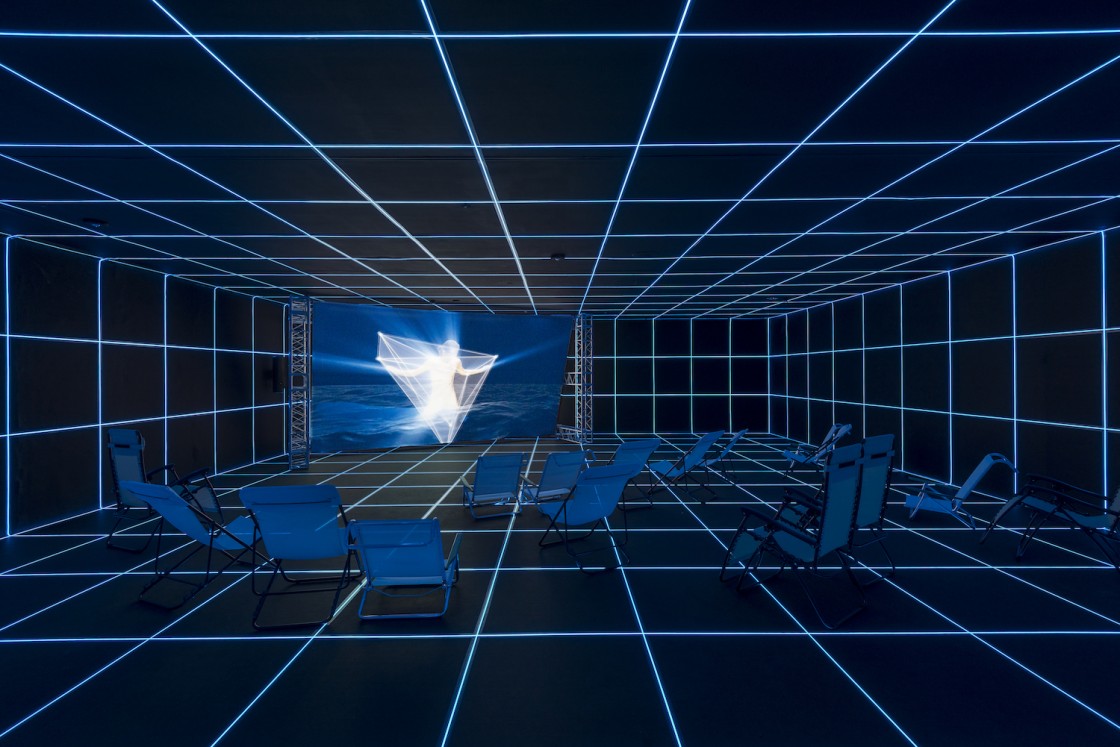

Digital cameras, and the technology that underpin them, are, like their film cousins, tools of expression and creation. Recording audio on tape was great. But I defy anybody to tell me that modern digitally recorded radio programmes like This American Life, Radio Lab or the Moth Hour, are not amongst the finest pieces of radio ever created. And some of the best art that challenges and critiques the issues Ritchen quite rightly raises (for example mass surveillance) are made digitally, for example by the likes of Hito Steyerl.

More interesting to me, and something Marisa Olson touches on in Lost Not Found: The Circulation of Images in Digital Visual Culture is how photography can bring meaning and insight from inside the digital realm. I had never encountered the work of the “pro surfers” which she describes as “copy and paste aesthetic that revolves around the appropriation of web-based content”. This feels especially relevant in our mid-Covid 19 world, where more of us are isolated from various aspects of the real world as never before, where nearly half of the UK workforce is working from home and where meetings are increasingly being held digitally online.

I was sad to discover the Nasty Nets blog had folded in 2012 (the article referenced above was published in 2008), but the kernel of its work has certainly not died and, combined with big data, has flourished in reflecting and documenting the growth of internet culture.

It brings with it efforts by the likes of AI academic James Bridle to explain, in Marie Chatel’s words: “the systems underlying artistic productions.

“By asking how artworks came to be and how they will evolve Bridle shows the partial understanding we get of these pieces through screenshots, video sequences, and other incomplete representations of processes.

“Mostly, New Aesthetics reviews the network itself, its rhizomatic structure, and modes of functioning — a technological apparatus that will become increasingly important to apprehend the arts.”

And modern computing power has made the impossible, possible. There are many ways of looking at issues of migration, for example. My esteemed colleague De is doing just that in her own work. But one of the finest pieces I have ever seen to bring home what refugee migration actually looks like is a data visualisation piece using almost unfathomably large amounts of data and shows a flow of humanity over time. It is astonishing.

https://www.lucify.com/the-flow-towards-europe/

As ever, new technology brings new fears, new challenges, new pitfalls but new opportunities to make sense of this world too.

References:

Ritchin, F. (2010). After photography. New York ; London: W.W. Norton.

Cotton, C., Klein, A. and County, A. (2010). Words without pictures. New York: Aperture ; London.

DANAE (2019). Net Art, Post-internet Art, New Aesthetics: The Fundamentals of Art on the Internet. [online] Medium. Available at: https://medium.com/digital-art-weekly/net-art-post-internet-art-new-aesthetics-the-fundamentals-of-art-on-the-internet-55dcbd9d6a5 [Accessed 4 Dec. 2020].

Risam, R. (2019) ‘Beyond the Migrant “Problem”: Visualizing Global Migration’, Television & New Media, 20(6), pp. 566–580.

The flow towards Europe – Lucify (2015). The flow towards Europe – Lucify. [online] Lucify. Available at: https://www.lucify.com/the-flow-towards-europe/.